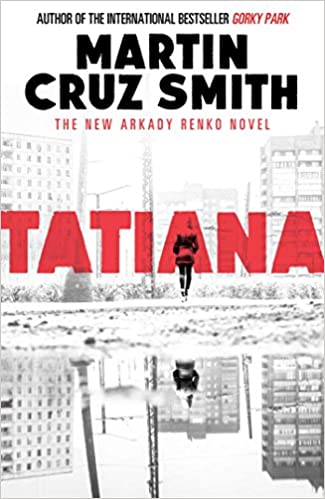

Tatiana is the 8th of Martin Cruz Smith’s Arkady Renko novels, all of which were re-packaged in 2013, with new monochrome photo covers and availability as ebooks.

The Renko novels go all the way back to their remarkable opener, Gorky Park published in 1981, during the dying days of the stagnant but, from this distance, strangely beguiling Brezhnev years. The most recent, The Siberian Dilemma, was published in 2019.

In several interviews over the years —for example in the New York Times in 1990— Martin Cruz Smith has talked about how he originally intended to write a novel about an American detective who goes to Soviet Moscow. Then the ‘obvious idea’ came to him; to make his hero a Russian detective. Arkady Renko was created.

Smith was not the only American writer to come up with that idea at that time, as 1981 also saw the publication, just after Gorky Park, of the first novel in Stuart M. Kaminsky’s Inspector Rostnikov series —a series which ran to 16 books before Kaminsky’s death in October 2009. (Kaminsky was credited by Sara Paretsky with helping her career through his role teaching a course on writing detective fiction.)

There are also a pair of English novelists who have written series about Russian detectives. Russianinfiction.com will get to them in the coming months. [This promise was kept with later reviews of the works of G.D. Absom and Ben Creed].

What all of these fictional Russian detectives have in common is similar to what most heroes and heroines of detective series have in common; they are inevitably maverick, and plagued by sceptical, duplicitous, time-serving bosses. It is just that when set in the Soviet Union, and even contemporary Russia, maverick becomes ‘dissident’, and duplicitous time-serving becomes ‘pro-regime’.

Both Smith and Kaminsky provide intriguing case studies of how the extraordinary developments in Russia since 1981 have been reflected in Western popular culture. Read the whole Renko series and you can follow him from Brezhnevian stagnation, through Gorbachevian reform, Soviet collapse, the rise of Yeltsin and the oligarchs, nostalgia for the days of Stalin, and —in Tatiana — the venal corruption of many in power during high Putinism.

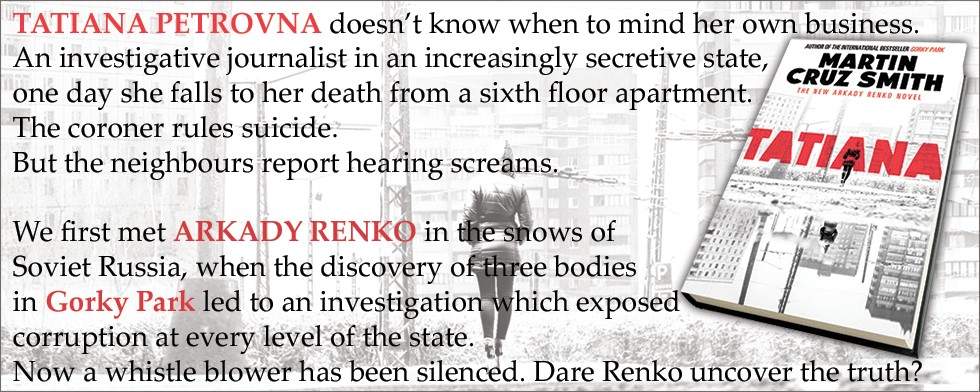

The publisher’s blurb on the publication of Tatiana, and the mini-relaunch of the Renko series that accompanied it, draws on such longevity.

Another thing of note about the Renko novels is that Martin Cruz Smith regularly takes his hero out of Moscow. Polar Star sees Renko on a trawler in the Bering Sea, Havana Bay takes him to Cuba, and Wolves Eat Dogs is largely located at Chernobyl with fascinating detail of the site of that nuclear disaster a couple of decades on. (A similar setting with similar detail can be found in Orest Stelmach’s 2013 debut novel The Boy from Reactor 4).

Tatiana keeps up this commendable originality, being largely set in the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, on the Baltic Sea between Poland and Lithuania. Somewhere I have never been, so I can’t comment too much on accuracy. Other than to say that the description of the brutalist Soviet style political headquarters known as ‘the Monster’ matches photos of the same.

Unfinished, unused, structurally insecure, a too-good-to-be-true metaphor for the project of ‘building communism’.

— ‘the Ninth Wonder of the World, the ugliest building of the Soviet era’ (p. 208), a metallic blue ‘headless elephant’ (p. 209).

The Kaliningrad setting ticks all of the appropriate boxes for that particular location —Kant’s grave, the Russian Baltic Sea fleet, the rather desolate dunes of its Baltic beaches, the border with Lithuania, and Kaliningrad’s fame for the production of amber (as exemplified in the mystery of what happened to the magnificent 18th century Amber Room removed from St Petersburg during the Second World War and never seen again; a story set out as fiction in Steve Berry’s thriller The Amber Room (2007) and as investigative journalism in Catherine Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy’s 2004 book of the same name).

As well as changes in temporal and geographical setting, the style of writing has changed too. The later Renko books have a more enigmatic approach than the earlier ones, achieved by shorter sentences, a tendency to eschew detailed description on occasion, and a willingness to let some of the major plot developments take place off page. Of the Renko series, Gorky Park remains the best known. (The 1983 film, with Helsinki standing in for Moscow, is good but does not do the book justice). My own favourite is Red Square, set at the time of the Soviet collapse.

From the Russia-in-fiction perspective, an interesting interview with Martin Cruz Smith accompanied the publication of Tatiana. How much on-the-ground research goes into the novels? How well does the author know Russia? He seems to visit the places he writes about, but not for long, and he speaks no Russian. Back in the Soviet era, his Renko books (Gorky Park and Polar Star) were not allowed to be brought into the USSR. Now six have been published in Russian.

Tatiana deals with familiar themes in western coverage of Russia in the Putin era, specifically the deaths of journalists who challenge vested interests, the Russian and Chechen mafia, and official corruption. The author provides a version of contemporary Russia which focuses, as of course crime novels do, on the underbelly.

‘What do you want? The murder of journalists, the beating of protesters, corruption at the top, the rape of natural resources by a circle of cronies, a fraudulent democracy, the erection of palaces, a hollow military … It’s all here …’

Tatiana, p. 263

Martin Cruz Smith drew on the murder of journalist Anna Politkovskaya in her Moscow apartment block when writing about the eponymous heroine Tatiana Petrovna’s murder.

‘She knew she was a marked woman. She was small but so dangerous to certain elements in the state that she had to be silenced, just as so many other Russian journalists have been intimidated, assaulted and murdered’ .

tatiana, p. 24

From the various potential explanations for the murder, such as the reach of organised crime or separatist extremists, in Tatiana it is the ‘certain elements of the state’ explanation for journalistic deaths that wins out.

Whether Smith was aware of the case of former Russian defence minister Anatoly Serdyukov when developing a plot which involves corruption in the Russian Ministry of Defence remains less clear, though the affair hit Russian news headlines in the year that Tatiana was published.

The plot of Tatiana revolves around the puzzle of a dead interpreter’s notebook, written in code, within which lies the secret of a criminal conspiracy. Happily such a puzzle is meat and drink to Renko’s adopted son and chess prodigy Zhenya. Alongside the puzzle, there is regular violence, and it all skips along to a somewhat hurried denouement.

The more recent Renko novels are as smart, original, and readable as their more substantial earlier stable-mates; but not quite as engaging, involving or ‘un-put-downable’. Tatiana is the shortest of the Renko novels.

From the perspective of my personal experience, there are a couple of great little details here which rang a bell and are typical of Martin Cruz Smith’s eye for the specific in his settings.

First, the phrase ‘when shrimp whistle’ (p. 67), used by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev (‘Those who wait for the USSR to reject Communism must wait until a shrimp learns to whistle’) and first mentioned to me as a test of linguistic skill by the legendary British government interpreter, the late Tony Bishop (1938-2012). Alastair Campbell’s diaries of the Tony Blair years said that Tony Bishop

… was wonderful to watch. He had done every Russian leader since Stalin and he seemed to take on some of the mannerisms of both sides as the conversation unfolded.

the blair years: extracts from the alastair campbell diaries, p. 249

And second, a brief description of Renko’s Moscow flat took me back to the central Moscow flat, just off Tverskaya Street (formerly Gorky Street), that I lived in for a few months in the early 1990s. It was a pre-revolutionary building and the most privileged location of anywhere I have ever lived.

Fellow residents told me that Stalin’s former chief prosecutor and show trial master of ceremonies, Andrei Vyshinksy, lived there in the 1930s. Not someone you would relish as a neighbour.

It is to that former abode I was taken when would-be assassin Fedorov comments, of the setting in which he is handcuffed to a radiator

‘Don’t you love these old apartments? High ceiling, fireplaces, parquet floor’

(Tatiana, p. 253)