When your choice of fiction is influenced by where it is set, then you can end up reading novels that you would not otherwise have given a second glance to. So far as Russia in Fiction is concerned, Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow is one such novel.

Russia in Fiction claims no special expertise in the literature of the prolific Paul Gallico (1897-1976), whose output of over 50 books ranged from The Poseidon Adventure, which was made into a blockbuster disaster movie, to children’s books much loved by Harry Potter author, J.K. Rowling.

Lacking such expertise, we turned to a website that is, in the words of its writer, ‘dedicated to the literature of Paul Gallico, one of my favourite authors’. Its conclusion with regard to Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow?

… it’s really not very good

http://www.paulgallico.info/mrsharrismoscow.html

That is a harsh conclusion. Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow is of a distinct type of story. If you want something comfortable, easy-to-read, and faintly ridiculous, then it is fine — it’s a cold Sunday afternoon, put the heating on, make a cup of tea, may be a slice of Dundee cake, and curl up on the sofa with Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow. That will while away an hour or so pleasantly enough, taking you to the attitudes and assumptions of England in the 1970s, and to a view of Moscow and the Soviet Union through that particular lens.

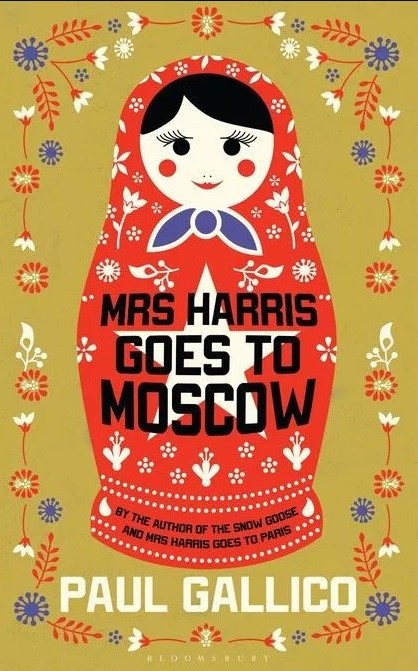

So redolent is Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow of the 1970s that Russia in Fiction did a double-take when discovering that it had been re-issued by Bloomsbury in 2012. Formerly a small independent publisher, Bloomsbury were enriched beyond what they must have imagined by their astute decision to take a punt on Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, a children’s book by an unknown author that had already been rejected by several other publishers. It would be fascinating to know whether J.K. Rowling had any influence on Bloomsbury’s decision to re-publish Paul Gallico’s ‘Mrs Harris’ series.

Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow is the fourth and final in Gallico’s occasional series of books about the adventures of Mrs Ada Harris, a widowed London char woman. It was preceded by Mrs Harris Goes to Paris (1958), Mrs. Harris goes to New York (1960), and Mrs. Harris, M.P. (1965). Their US titles —in full Mary Poppins-esque, Cock-er-ney pronunciation style— chose to drop the ‘H’, as in Mrs ’Arris Goes To Moscow; and, to make things a little clearer Stateside, replaced Mrs Harris, MP with Mrs ’Arris Goes to Parliament.

(And as if all that is not confusing enough, do be careful not to muddle up Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow (1974) with Miss Bagshot Goes To Moscow (1961), written by Anne Telscombe, who is the author of the book reviewed directly before this one in Russia in Fiction’s progress towards 100 reviews.)

Gallico’s story is straightforward and well-constructed, and it moves along at a fair old pace to its conclusion within 200 pages. Worldly-wise char woman Ada Harris picks up a framed photograph of a beautiful Russian girl, Lizabeta Nadezhda Borovaskaya, whilst dusting in the home of a writer, Mr Lockwood. Lizabeta and Lockwood met and fell in love when the writer was in the Soviet Union, carrying out research for his new book Russia Revealed.

As was the real-life fate of too many couples caught in such East-West relationships, the Soviet authorities would not let Lizabeta leave the country. (Owen Matthews wrote about his parents’ troubles in this regard in Stalin’s Children (Bloomsbury, 2009)).

The British authorities are not inclined to assist Mrs Harris’s bereft writer

Lockwood spoke bitterly. ‘The two faces of Russia,’ he said. ‘Come to Leningrad and Moscow. See the Golden Carriage in the Kremlin, the mummy of the great god Lenin and the relics of the Czar. Vodka, caviar, coddling. Intourist putting its best foot forward to pull the wool over the eyes of the West and behind the smiling mask the cruellest and most treacherous people on earth …

Mrs Harris asked, ‘What about your pals in the Foreign Office? Didn’t you say that …’

She only succeeded in rekindling the moment of rage in Lockwood and he slammed the desk with his fist and shouted, ‘Goddamn bloody hypocrites! … “Sorry, old boy, can’t rock the boat right now, you know.”‘

mrs harris goes to moscow, pp. 11-12

Being the sort of woman she is, and featuring in the sort of novels she does, Mrs Harris happens (or may be Mrs ’Arris ’appens) to win a pair of tickets for a package tour to Moscow. And so Ada Harris and her friend Mrs Butterworth fly east, with the former intent on helping her employer, lovelorn Mr Lockwood.

Nonsense, for sure. Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow is replete with coincidences and caricatures. But of course caricatures are grist to the Russia-in-fiction mill. We are all about how Russia is perceived.

For all its farce-like feel, Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow does reveal the dominant themes and experiences that a Western visitor to Moscow in the 1970s might note. Presumably Paul Gallico went on an Inturist package such as that enjoyed by his characters? He writes of the disorientation visited on a couple of working-class British women when arriving at Moscow’s Sheremetevo airport.

… every sign in a wholly unintelligible foreign alphabet, the Cyrillic lettering. Different sounds, different smells, a kind of combination of cheap soap and disinfectant and the clothes basket containing last week’s wash, different tempo, rude and hard looking officials, lumpy sheep-like ill-clad crowds

mrs harris goes to moscow, p.69

There is a charming account of the awe felt by Mrs Harris when she looks out of her fictional central Moscow hotel window (presumably what was then the National and is now the Marriott) …

… on to an extended part of the formidable Kremlin wall, St. Basil’s Cathedral, the tomb of Lenin and Red Square. Night had supplanted dusk, lighting was in full blaze and she found herself looking upon such a wondrous illumination of coloured walls, towers, belfries, church steeples, some shaped like onions, others wearing what appeared to be Oriental turbans, all flung into the night sky and staggering to the imagination. Giant red stars gleamed from tower pinnacles, the bulbous tops of the churches were picked out in ultramarine blues and bright yellows. Some were smoothly curved, others rough like pineapples piled one atop the other. The part of the vast square visible from her vantage shone like a floodlit pool. Light glittered from distant buildings. Mrs Harris, with not too many points of reference, could only think of it as a combination of a bejewelled fairy city and an amusement park with only the rollercoaster and other thrill rides missing.

She was genuinely moved by the sight, moved to murmer, ‘Cor blimey, but ain’t it beautiful,’ and felt suddenly glad that she had come.

mrs harris goes to moscow, pp. 82-83

Mrs Harris’s enthralled reverie is interrupted, as if in confirmation of Lockwood’s bitter denunciation of the two faces of Russia, by her companion Mrs Butterworth emerging from the bathroom, complaining

‘There’s no loo paper … And what’s more there ain’t no stopper for the barftub. The ‘ot water runs cold and the cold water runs ‘ot and the shower don’t run at all. When yer pulls the flush nuffink ‘appens. Yer call this a ‘otel?

… And call them there rags, towels? Fly specks on the mirror and the light bulb don’t work. First class accommodations, eh? And us wif paid-up tickets. Let’s get on the blower and ‘ave a little word wif somebody.’

mrs harris goes to moscow, p. 84

Such is the flavour of the book. And there is much more where that came from. All the clichés are rolled out — a fearsome dezhurnaya (duty woman) stationed outside the lifts on every floor of the hotel, the lack of a Western-style service culture, the rules as to what was and was not allowed of guests.

Plot-wise, Keystone cop KGB officers mistake a char lady as Lady Char, an aristocrat and therefore clearly a spy. Different Soviet organisations argue over who has authority in relation to foreign visitors. The British Foreign Office, helped by a sympathetic Russian diplomat, finally get their act together, and all ends in the way that such easy-reading should.

Russia in Fiction has no further reason to trouble ourselves with any other of the Mrs Harris novels, but we are not unhappy that we read this one. Mrs Harris Goes To Moscow will not detain any reader for long, and its one-sitting length provides a harmless and pleasant diversion back to the brown and orange decade that was the 1970s.