Part two of this review is here.

The Useful Idiot tells a tumultous tale that entertains amidst the terror of its subject. It is a story of duplicity and dupes.

Set in Stalin’s Soviet Union in the spring of 1933, The Useful Idiot is based on the real life story of a short but significant visit to Moscow and Ukraine by Welsh journalist Gareth Jones (1905-1935).

Jones was one of the few Western journalists not only to report from the Soviet Union, but to report accurately what he saw. Instead of taking what the Soviet authorities fed him, and passing it on to his readers in the West; Jones —like the novel’s author, John Sweeney— merits the term ‘investigative journalist’.

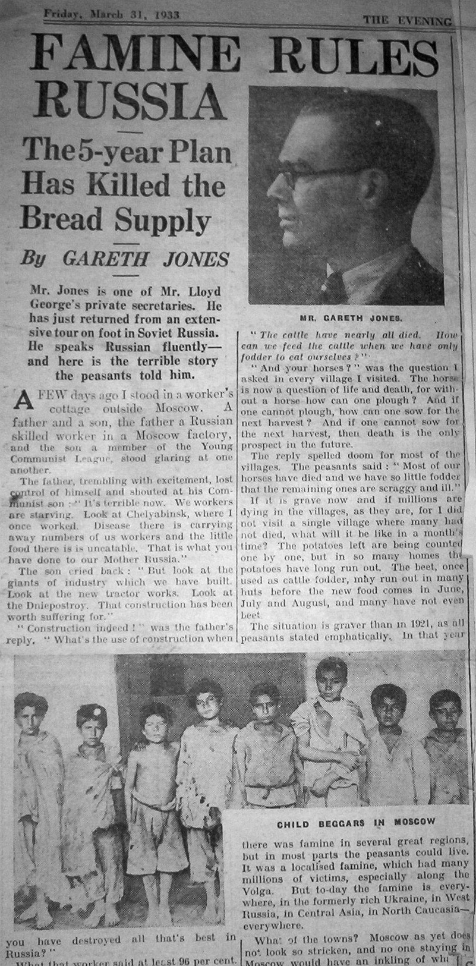

Gareth Jones reported what he saw; famine in Ukraine, corpses in the streets, and the devastation wrought by the policies of the Soviet state.

Partly spurred by family feeling —as his mother had lived and worked in the Ukrainian city of Hughesovka, now Donetsk, in the early 1890s— and mainly driven by a determination to investigate rumours of famine, Gareth Jones went where his Soviet minders did not intend.

When he returned to Britain, he published widely and lectured frequently on his experiences in the Soviet Union; not just as a witness to famine, but on living and working conditions in Moscow, the terror of the secret police, and the Metro-Vickers trial, which happened to coincide with his time in the Soviet capital.

There has been something of a surge of interest in the life of Gareth Jones in recent years. The movie Mr Jones was released in 2019. Ray Gamache’s academic study Gareth Jones: Eyewitness to the Holodomor was published in 2013. There is a 2021 publication date for Mr Jones — The Man Who Knew Too Much: The Life and Death of Gareth Jones by Welsh political journalist Martin Shipton.

And the family of Gareth Jones has done a good deal of work bringing details of his life and work to public knowledge, through two books and a detailed website.

Prompted by reading The Useful Idiot, I read More than a Grain of Truth: the biography of Gareth Jones (2005) by his niece Dr Margaret Siriol Colley. This gives the whole scope of Jones’s short life, intersecting with the vicious impact of totalitarianism in Europe in the early 1930s.

Most famous for his brief time in the Soviet Union, Jones was even better acquainted with Germany, and had been in a plane with Hitler and Goebbels, flying to a Nazi rally a few days after Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor. Jones spoke German and Russian. He spent a year in the United States as the Great Depression bit.

Jones was shot in Mongolia, a day short of his 30th birthday, in August 1935. According to John Sweeney, in the Author’s Note to The Useful Idiot, Gareth Jones ‘was killed in China at the orders of the Soviet secret police — payback for his efforts to tell the truth about the famine’.

And so, I eventually get back to The Useful Idiot. Clearly whole books and films could be, have been, and deserve to be written about the remarkable Mr Jones. But this is the Russia in Fiction blog — we review fiction set in and concerning Russia and the Soviet Union. We ask two questions: what is the book like? and how does it portray Russia?

The Useful Idiot reads as a thriller. It zips along with clear characterisation, well-spaced revelations, betrayal, sexual tension, and classic spy-thriller scenes such as assassination, being followed by the secret police, narrow escape, a race across the Soviet Union. Reading it before much awareness of the Gareth Jones story, and before watching Mr Jones the movie, I read it for what it is, and enjoyed it to the end.

The Useful Idiot, as a title, redirects the reader. The novel’s hero, Gareth Jones, is not really the titular hero in that he is no ‘useful idiot’ in the classic use of that term; quite the reverse. The term ‘useful idiot’, often misattributed to Lenin as its source, refers to westerners whose ill-advised and naïve support for bad regimes serves to bolster them; infamously in the Stalin years, people like George Bernard Shaw and Sidney and Beatrice Webb.

There was a BBC World Service series in 2010 in which John Sweeney presented a programme on Stalin’s western apologists, so he certainly knows the term and its context.

But Sweeney nonetheless has his fictionalised Gareth Jones guiltily ascribe himself the term, after his naïvety about the brutality of the Soviet secret police results in the arrest and torture of an acquaintance. More straightforwardly, the novel’s title makes the reader look not just at Gareth Jones, but at the cohort of the western journalists and diplomats who denied what was in front of their faces.

Part two of this review is here.