The standard unit of measurement for writers of spy fiction is ‘the Le Carré’. Almost any half-good new espionage writer gets some blurb on the back of their book calling them ‘the new Le Carré’.

Besides being the only espionage writer whose name rhymes with Le Carré, McCarry, who died in 2019, was one of the few to merit the comparison in terms of quality, and indeed of style.

The preliminary material in my paperback re-issue (2012) of The Secret Lovers contains a selection of ‘Praise for CHARLES McCARRY’ which gives a fair idea of his standing.

‘Ranks up there with Le Carré in a select class of two’ – Daily Mail

‘As a storyteller, McCarry surpasses Len Deighton and John Le Carré’ – The Washington Post

‘The absolute best thriller writer alive’ – P.J. O’Rourke

There is no need to decide whether McCarry is better than Le Carré. It is enough to confirm that the comparison at least stands up to scrutiny in terms of literary skill, complexity of plotting, nuances in characterisation, background in the security services, and —almost— longevity.

McCarry’s George Smiley is Paul Christopher, the central character in 10 of his novels, of which The Secret Lovers is the third. Its title has a pleasing ambiguity, its plot a pleasing intricacy.

Christopher becomes responsible for overseeing the publication of a novel written by a Russian dissident, which has the potential to seriously undermine the Soviet regime. The fact that the courier who brought the novel West is killed in a hit-and-run only minutes after the handover with Christopher raises doubts from the start over who is seeking to manipulate whom.

As an ex-CIA man, McCarry knows how things work on the ground. I love his take on tradecraft surrounding the death of the courier. He inverts all notions of staying safe by checking that you are not being followed, arguing instead that excessive tradecraft has the opposite effect.

Bülow drew danger to himself by the excessive use of technique; he behaved like a spy because he enjoyed the trappings of conspiracy. He had been making the same furtive mistakes for such a long time that he believed they had preserved his life. No one else doubted that sooner or later they would kill him

the secret lovers, p. 2

The ‘trappings of conspiracy’, and their reliability or not, play an interesting role in the novel’s plot, as it becomes apparent that a trusted US spy has never been ‘fluttered’ (undergone a lie detector test).

Tradecraft terms such as ‘fluttering’ and ‘chicken feed’ (information that is genuine but of little importance given to the enemy by an agent to prove their bona fides) are common in espionage fiction. But more original is the verb to ‘redouble’ —as in ‘what if he redoubles her?’ (meaning to tempt a double-agent to switch sides a third time, p. 83). It tickled me, and illustrates McCarry’s facility with the well-written phrase.

I was drawn into The Secret Lovers too by its settings. The plot is played out in Berlin , Paris and Rome, and it is always a pleasure to read a book whose precise locations are familiar to me.

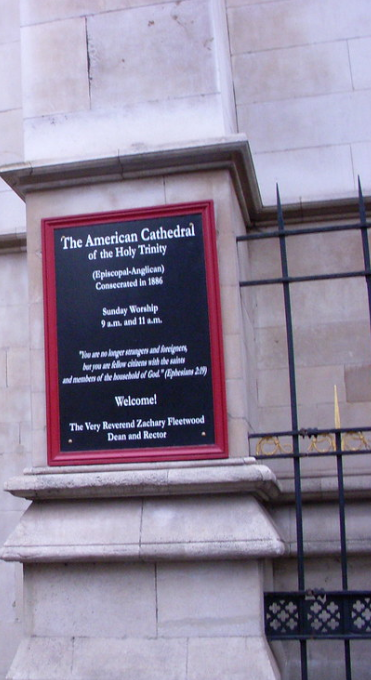

In Paris the ‘elementary tradecraft’ of leaving a chalk mark to signify a pre-agreed message sees that mark being left on the stone wall of the American Cathedral on Avenue George V —a location where I once spent a day in meetings as the alphajets of the Patrouille de France aerial display team flew an ear-splitting rehearsal for the Bastille Day celebrations past the open windows.

And I was immediately transported back to an evening in Rome by Christopher’s night-time taxi journey from the airport into town, when he

rolled down the window of the taxi. Even at four in the morning, the air was balmy and he could smell the earth of the farmlands along the Via Ostiense

The secret lovers, p. 55

Arriving at Rome’s Fiumicino airport one night a few years back, I bumped into an acquaintance, a Scandinavian diplomat then serving as ambassador in another European country. We decided to share a taxi into the city centre.

The taxi took off at a fair old speed, zig-zagging from lane to lane as Italian drivers are stereotypically supposed to do. I had not realised until then that my companion was a nervous passenger. As the journey went on, the taxi driver hurtled us past trucks, undertook more sedate drivers, and flashed his lights impatiently at tiny Fiats impeding our progresss.

My companion was becoming increasingly distracted, gripping her briefcase and letting out nervous gasps, muttering under her breath to me

Should we tell him that we’re not in a hurry? Why is he going so fast? I’m going to tell him …’

Eventually, she could take it no more. She leaned forward, tapped the driver on the shoulder, and told him that he should go slower. Somewhat taken aback, he apologised and applied the brakes a little.

But I could tell our driver wasn’t happy. Something was perplexing him, frustrating him even. A few kilometres further up the road, he had finally worked it out. Turning round, he looked at us and proclaimed, with a smile of revelation on his face,

Heh! This is Roma!

… before once more putting his foot down and continuing our exhilarating journey into that most exhilarating of cities.

To complete the tour of great western European capitals, The Secret Lovers takes us fleetingly too to Madrid. But it is not really Madrid that is of interest, but the Soviet Union’s role in the Spanish Civil War, which feeds into McCarry’s plot.

That war’s brutal complexities saw two totalitarian regimes (Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union) supporting opposing sides. But, as McCarry skilfully sets out, Stalin’s support was —like the man himself— conditional, suspicious, and self-interested. It was not just a matter of supporting the socialists against the fascists. They had to be the right sort of socialist; certainly not Trotskyites. And Russians in Spain in 1936 were watched over by the NKVD (the forerunner of the KGB).

McCarry introduces a fearless Russian Communist journalist called Zhigalko.

It was no wonder that the NKVD worried about Zhigalko. To him, they meant nothing. Kolka Zhigalko was a Communist, almost an old Bolshevik, he had gone to war with the Red Army in his teens. But he had been formed, like all Russians, in the Church and in the language and in those vast spaces of mystical Russia that everyone always uses to explain the fatalism of the Russian character.

the secret lovers, p. 255

McCarry’s use of the term ‘Old Bolshevik’ —signifying someone who joined the Bolshevik Party before the revolution, and therefore had a genuine belief in its cause as opposed to merely jumping on the careerist bandwagon once the Party was in power— demonstrates a sound knowledge of Soviet history. And his emphasis on the power of Zhigalko’s Russian-ness, lying beneath his ideology but not wiped away by it, represents a common notion in many attempts to explain the nature of the Soviet regime —from Boris Pilnyak’s wonderful novel The Naked Year, to attempts within the US government and security apparatus in the Cold War years to develop behavioural analyses of the Communist leadership.

Although it is not set in Russia, The Secret Lovers knows its Cold War setting very well, and as ever McCarry produces an intelligent, original, and immensely readable work.