Part one of this review is here

Key to many a thriller/crime writer’s success is the creation of a memorable lead character. Martin Cruz Smith has his Arkady Renko, Boris Akunin his Erast Fandorin, and even John Le Carré returned again and again to the enigmatic George Smiley. Tom Clancy did not simply create such a character, he created a dynasty and alternative history.

Clancy’s Jack Ryan rose, across a series of novels, from CIA analyst to two-term US President. There then followed a series of novels about Jack Ryan Jr., continued after Clancy’s death in 2013 with varying degrees of quality across multiple authors. Jack Ryan movies are multiple, and there is a Jack Ryan Jr. TV series.

In The Cardinal of the Kremlin —the third novel to feature Clancy’s signature character— we meet CIA analyst Jack Ryan as part of an American delegation to Moscow, charged with negotiating an arms control treaty. The US side are sceptical of any Soviet concession.

In US-Soviet arms negotiations, realism had always trumped idealism. No side ever gave up anything simply because it was ‘the right thing to do’. It was always about trade-offs. So when the Soviet side makes cautiously generous offers with regard to missile reduction, the US negotiators wonder why.

To some degree, The Cardinal of the Kremlin provides a fine example of how the fast-moving events at the end of the Soviet era caught out not only most analysts, but also, most thriller writers. At about the time that Clancy’s novel was being published, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was astounding the West by making some genuine and significant unilateral cuts in his 1988 speech at the United Nations in New York.

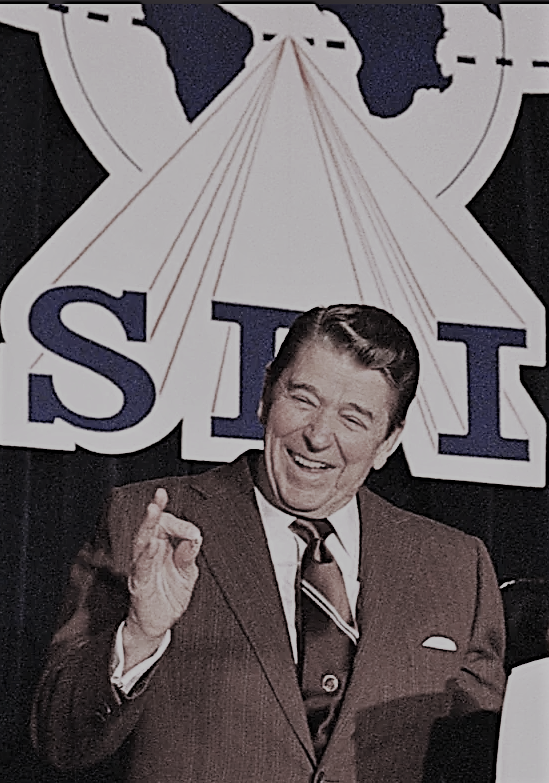

Back in the world that Tom Clancy was imagining, the reason behind the Soviet offer of concessions relates to that other key element of the superpower arms race that was to the fore in the 1980s, namely, SDI, the Strategic Defence Initiative.

SDI —known colloquially as ‘star wars’— envisaged the US being able to shoot down inbound Soviet nuclear missiles.

Behind the seemingly counterintuitive notion that world peace could be ensured by a buildup of nuclear arms by both superpowers was the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction; the idea that neither side would launch a nuclear war because to do so would be to ensure their own annihilation alongside that of their enemy. If one of the superpowers could develop a sufficiently reliable defence against nuclear weapons, then this macabre balance might disappear.

President Reagan abhorred the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction, and in his SDI speech of 1983 he looked forward to a day when the ability to defend against ballistic missiles would render nuclear weapons ‘impotent and obsolete’.

From the Soviet perspective, such advances in military technology might prove disastrous in that the USSR owed its own superpower status almost entirely to its standing as a nuclear power.

For a fascinating account of Reagan’s personal role in all this, have a look at the PhD thesis by the appropriately named Ciaran John Ryan, available here, p. 177ff.

In The Cardinal of the Kremlin, the Soviet Ministry of Defence realises that

an American strategic defense system could negate all of the Soviet nuclear posture …

And that meant that all of the billions that had been sunk into ballistic-missile production were now surely wasted as though the money had been dumped into the sea.

the cardinal of the kremlin, p. 161

But fortunately, both for the fictionalised USSR and for the plot of this novel, in The Cardinal of the Kremlin the Soviet Union is developing its own equivalent to the Strategic Defence Initiative, both sides are nearing technological breakthroughs, and both sides have spies with access to the secrets of the other.

Alongside this central plot element, the Soviet war in Afghanistan has a related plot line of its own.

Tom Clancy was a masterful thriller writer, particularly when painting big picture, wide canvas scenarios. He was —at this stage of his career at least— factually accurate when it came to portraying real-world developments, although, as noted above, sometimes such developments outpaced their fictional representations.

Factual accuracy was strong ‘at this stage’ of Clancy’s career, but —as any Clancy aficionado knows— as the novels in the Jack Ryan series progressed, Clancy decided that for credibility from one novel to the other, the events that he had depicted in one book had to be treated as genuine in the following books.

For example, when a rogue Japanese nationalist flies a plane into the US Capitol building in 1994’s Debt of Honor, then this cannot be made to have un-happened in subsequent novels. So what has become known as the ‘Ryan-verse’ was created and took on a parallel existence in Clancy’s novels alongside global events.

What about Tom Clancy’s knowledge of Russia? On one level it does not need to be that deep. We are dealing here with élite level politics for the most part, and he does this well.

From the first paragraph, Clancy’s descriptions of a diplomatic reception in the Kremlin ring true.

The setting is the St George Hall of the Great Kremlin Palace, and the descriptions of the various types of people milling around — diplomats, politicians, military, reporters, and spies— reminded me of such events.

A quartet of strings in a corner play chamber music to which no one appeared to listen, but this too is a feature of diplomatic receptions and doing without it would be noticed.

the cardinal of the kremlin, p. 25

Reading that took me back to a dinner I attended about a decade ago in the British Consulate in St Petersburg (which incidentally no longer exists since it was closed down in the wake of the Skripal affair in 2018).

It was not even a particularly grand occasion —a visit from the Lord Mayor of London, with accompanying trade delegation— and I had been invited along just because I happened to be in town. After the meal, three opera students sang to us, beautiful singing but all rather incongruous and loud in the relatively small confines of that particular dining room.

Overall, The Cardinal of the Kremlin served me well nearly three decades ago, when many weeks spent alone in Moscow were enhanced by thick thrillers with complex plots to while away freezing winter evenings. Re-reading it in sunny lockdown Lincolnshire was not quite the same experience, but nonetheless this remains one of Clancy’s best.

Part one of this review is here