Part Two of this review is here

‘Rancid Aluminium: The worst film ever made in the UK?’

Wales in the Movies YouTube Channel

Rancid Aluminium was very well reviewed. For my part, well, it is not my sort of thing, although I can tell it’s well written. It is always possible that I was subconsciously biased against the book by the fact that I saw the film, screenplay also by James Hawes, released in 2000.

As I write this review in 2020, I have come across a 15 minute vlog made this year (on the ‘Wales in the Movies’ YouTube channel), which carefully critiques Rancid Aluminium the movie, under the title: ‘Rancid Aluminium: the worst film ever made in the UK?’

Put Rancid Aluminium in a search-engine and you will see that it is broadly accepted that Rancid Aluminium the movie, despite its British A-list stars, is awful. And I have not only watched it, I remember making a rare trip to the cinema, to pay money and sit with about two other people in the whole place, slightly aghast.

James Hawes, the author of both the original book under review here and the screenplay of the film, has acknowledged the movie’s poor reception in interviews since. To his credit he self-deprecatingly makes the central character of one of his later novels the ‘co-producer of the ghastly Britpack Russian Mafia caper Base Metal’, as the back cover of White Powder, Green Light (2003) puts it.

But Russiainfiction.com reviews books not films. And if the accepted view of movie reviewers is negative so far as Rancid Aluminium is concerned, the opposite can be said of the book’s reception.

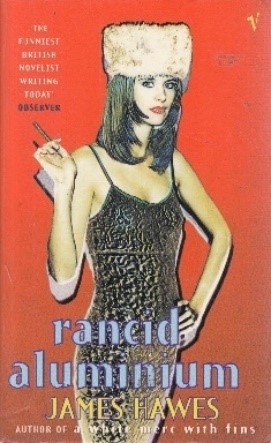

Rancid Aluminium was very well reviewed, and those reviews —quoted at some length on front and back of my paperback copy— focus on the comedic angle. The line quoted from The Observer represents review gold for the publisher:

‘the funniest British novelist writing today’.

Euan Ferguson

Cosmopolitan called the book

‘a hilarious black comedy’

The reviewer from The Times gushed about how it made her laugh until she cried and could not breathe.

Talk about the back-cover blurb setting the bar too high.

For my part, like I said, it is not my sort of thing. I acknowledge its clever phrasing and construction, and these even occasionally brought a smile of admiration, but it didn’t make me laugh out loud, let alone struggle to breathe. Absent the reviewers’ quotations, I am not sure I would have even realised it was supposed to.

Rancid Aluminium is a well-plotted novel with some cleverly drawn characters and memorable scenes. I read it, of course, because of its Russian elements.

The front cover has a photo of a beautiful woman wearing a fur shapka, and on the back cover there is a photo of a young man in shades dressed like a Russian gangster from the last decade of the 20th century.

The hero of Rancid Aluminium, Peter Thompson, runs a small business based near the Charing Cross Road in London. Largely because he hasn’t been paying all his taxes, Peter is faced with his business going bust, at the same time as his relationship with Sarah is reaching the stay-or-go stage of commitment and the possibility of children.

Financial salvation seems available when a larger-than-life, super-rich Russian ‘businessman’, helpfully called Mr Kant, offers a huge loan at a very low rate.

Of course the reader knows that it is all too good to be true. Of course Peter Thompson does not:

the moment it all started, remember? Chernobyl-time. The moment Deeny, my smarmy Irish accountant, called me up on the mobile.

Rancid Aluminium, p. 32

Mr Kant —homophonically named if, as I imagine Peter Thompson does, you have a ‘Sarf London’ accent— is a Samara-based Russian businessman who is archetypal. In the first chapter he rolls into a small town in southern Russia in his black Mercedes.

A uniformed driver, well over six feet tall, got out, strode around and opened the back door. After a pause, the man in the back stretched a black wool-clad leg out into the rain, allowing his long black sock and shining black shoe to be seen for a moment in all their clearly Western glory. Then he planted his foot demonstratively in the middle of the deep puddle before which, inevitably, his door had ended up.

Rancid aluminium, p. 6

Kant wears a black cashmere overcoat and distributes dollars —in this case directly into the coffin of an unfortunate victim of a Mafia feud— in exchange for ‘good business’. He is the dominant figure at any table, and, as well as dollars, he distributes his own wisdom and knowledge, or even cant, gained in the tough school of Russian life in the late Soviet and early post-Soviet years.

In his big London house Mr Kant puts forward his views on England, and on the Englishmen whom he most admires — the Elizabethan explorers, Drake and Hawkins.

“Men who set sail with an 80 per cent chance of dying and 10,000 per cent profit if they came home. Those were the businessmen he admires, men who dealt with cannibal Chiefs as Local Kings and Lords; men who had never heard of Nationalism or Racism; men who saw other men as trading partners, no more, no less …

Men of hard enlightenment!

…

These were Englishmen. And everything good about England became what? America …

You think Mr Kant should love the Burlington Arcade? Huh? You think he must adore Stiff Upper Lips and Fair Play? Mr Kant scorns all that. These are things for neurasthenic faggots. The England Mr Kant adores is the England that came free booting out of the Northern fogs and in two centuries opened up half the world to Free Trade.

What infertile bureaucrat’s crypto-Jesuit dreams of the Perfect State, what beer-sodden Hegelian drivellings of World-Historical Forces, what Stalinist mathematician’s death-wish fantasy of a Plan to end History can match the grandeur of England’s unplanned drive to freedom, to America?

Long live the Free Market and Anglo-Saxon financial institutions! Drake and Hawkins!

rancid aluminium, pp. 118-119

And, as is the oligarch way, Mr Kant has a secretary who is ‘the most beautiful woman in the world’ (p. 105), and with whom Peter Thompson becomes obsessed.

Part Two of this review is here