Russia in Fiction has noted before that when you choose your reading based on whether a novel engages with Russia or not, you end up reading genres that might otherwise have passed you by.

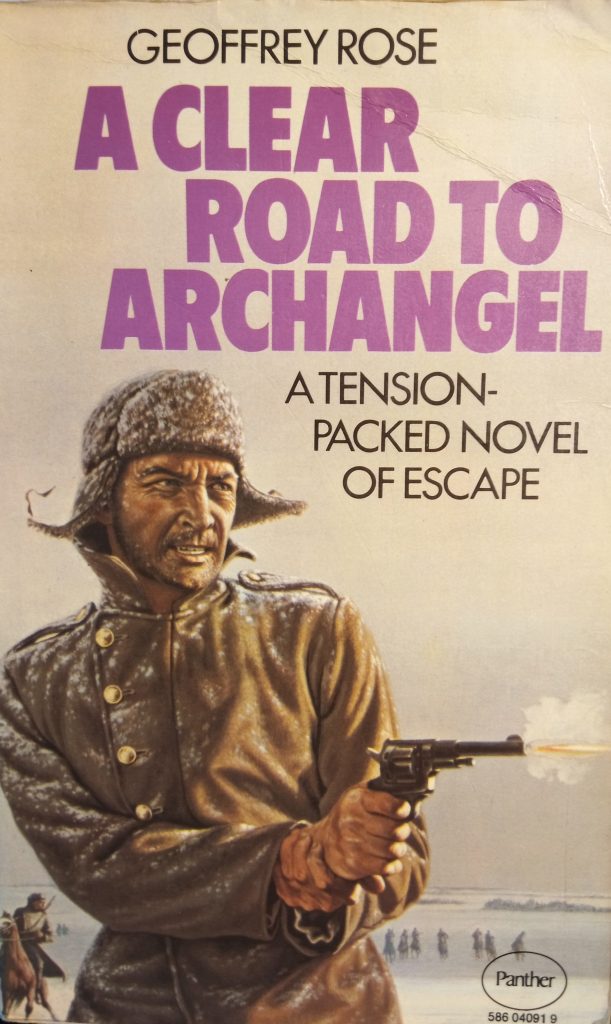

Geoffrey Rose’s A Clear Road To Archangel sits on the edge of such a situation. It is a thriller and such are this blog’s staple diet, even as we endeavour to vary the menu with regularity. But beyond the thriller meta-genre, A Clear Road To Archangel fits into the so far neglected ‘man on the run’ sub-genre.

The book’s unnamed first person narrator is a British spy, caught up in the convulsions of revolutionary and Civil War Russia, and trying to find his way to Archangel (Arkhangelsk) in the far north. If he can get there, he is confident of rescue by British forces or their allies.

Though the ‘if he can get there’ is not quite right. For some reason, Geoffrey Rose chose to write his novel as if it were a memoir pieced together decades later. The reader knows from early on that the man did make it to Archangel and escaped.

Geoffrey Rose is an actor turned author, who wrote three novels in the mid-1970s, of which A Clear Road to Archangel seems to be the best known, and is the only one set in Russia.

We meet the novel’s anonymous hero hiding under a bridge in the snow somewhere in the Russian countryside in late 1917 or early 1918. The uncertainties are deliberate, as the man is unsure of his precise location or the date. He is a British spy sent into post-revolutionary Russia in the final year of the First World War because

the British Government wanted to be assured that our ally, who had looked as lifelike as a well-made snowman and proved about a forceful, having melted from our side would not materialise on the other

A Clear Road to ARchangel, p. 9

Having been captured and tortured by an English-speaking, Dickens-reading, calmly psychotic Russian officer known as Captain S., the narrator of A Clear Road To Archangel has managed to escape. He has only one plan —to head north to Archangel. And the novel consists of his adventures in doing just that. It is a relatively short book, less than 200 pages, divided into two parts for no apparent reason as the distinction between them is not clear.

Geoffrey Rose writes well, with a slightly hazy style that reflects the fate of his central character, lost in the middle of nowhere and subject to haphazard fortunes of good and ill.

And what about Russia in the fiction?

The land itself provides an active setting, with the novel’s three-word opening sentence setting the scene.

There was snow. There was not more of it visible to me than I’d seen in England, but a sense of the infinitude I couldn’t see, going on for ever across the steppes, made of the Russian snow a different element.

A Clear Road To Archangel, p. 7

Basic as it may be, I have been known to begin university courses on Russian politics by reminding students that Russia is big and cold. It explains a lot. And in A Clear Road To Archangel, climate and vast expanse stand high on almost every page as the man heads north, mostly on a succession of stolen horses, and —one time each— by train, barge, and motor car.

And alongside the meteorological and geographical character of Russia, there is the temporal character of a country in military and political chaos as the Russian Civil War begins to take shape from within the embers of the First World War. Whites and Reds. Faded aristocrats and desperate peasants. Germans and Americans. The man meets them all, and on each occasion finds either danger or succour.

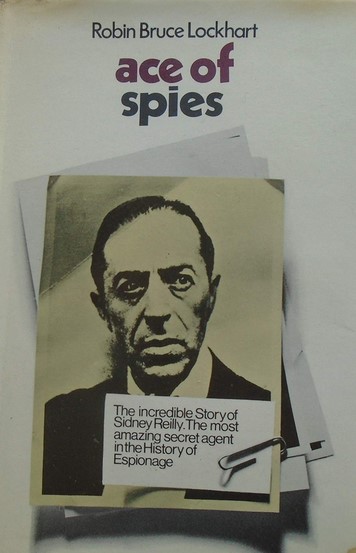

Historical parallels can be found between the story in A Clear Road To Archangel and the real-life case of Sidney Reilly, the subject of the book Ace of Spies (1967) by Robin Bruce Lockhart, which became a BBC TV series of the same name in 1983.

Amongst his decades of espionage-related adventures, Reilly’s involvement in an attempted coup against the Bolsheviks in 1918 stands out. After any coup plans failed, Reilly’s colleague proposed an escape route out of Russia that went south via Baku, but Reilly instead chose to head north towards Finland. This is essentially the route taken in A Clear Road To Archangel, and as happened to Reilly, the man’s journey north is made more difficult by ‘wanted’ posters with his photograph being distributed in the area through which he travels.

Geoffrey Rose appears to have combined elements of the story of Sidney Reilly with the events of August 1918, when British warships, carrying almost a couple of thousand British and French troops, landed in Arkhangelsk to support an uprising against the nascent Bolshevik government.

These actions formed part of the Northern Russian Expedition, which brought allied troops, including Americans, into conflict with Bolshevik forces in late 1918 and well into 1919. Fierce fighting chiefly involving the British army —in loose coalition with increasingly disorganised and divided Russian allies in the anti-Bolshevik ‘White’ forces— met more than had been bargained for as the Red Army repulsed the expedition.

Eventually, 102 years ago this week, in late September 1919, the remaining British troops escaped from Arkhangelsk by ship.

A Clear Road To Archangel makes no direct reference to these historical events. Unlike Sidney Reilly, its central character speaks no Russian, despite being sent into the heart of revolutionary Russia by the British. Presumably Geoffrey Rose preferred the creation of narrative tension over alignment with reality.

There are only two Russian characters who step out of the anonymous narrator’s miasmal memoirs. One is Captain S., his torturer, who reappears at different points of the narrative journey; each time embodying some element of the changes ripping apart the old order. He may have started off as an officer in the Tsar’s army, but —like many— he then has to decide, or be forced by circumstances into choosing, where his interests lie. With the Red Army, supporting the new Bolshevik government? With the Whites, resisting the revolutionary takeover? With foreign forces, intervening in events as the First World War comes to an end? Whichever side he is on —and as ever the narrator is not always sure— Captain S. remains the novel’s villain.

The other Russian to be drawn as a full and rounded character is ageing aristocrat Grigor, remaining almost oblivious to world-shaking events as he carries on life as normal on his estate somewhere in northern European Russia.

Grigor reminds Russia in Fiction a little of Goncharov’s hero Oblomov, from the novel of that name published in 1859, who live his provincial, well-off life in his own world, despite the darkening clouds of change becoming apparent around him.

Grigor welcomes the man into his mansion and treats him as an old friend whilst he regains his strength on the journey to Arkhangelsk.

I write of him at length because of the many people I met in Russia he was the only one I knew, or at least had an opportunity of knowing. And because Russia has printed itself in my memory, a growing enigma, I try to read some clue in Grigor, who was at once the most and the least characteristic of her sons. He must have died long ago. He was a good thirty years my senior … Anyway he was too obvious a target for the new regime — too rich, too lukewarm a socialist, ‘nice’ to his serfs, too aware of the West. I don’t know what happened to him and I don’t wish to. I prefer to remember him as he was then. Whatever happened afterwards was irrelevant. Almost certainly it would have provided the hardship he sought, and possibly he found in it a semblance of salvation. I don’t fancy he would have lasted long in a labour camp; but I can believe he might have lit his end by some act of kindness or even heroism. So he may have realised his dream of riding out at dawn.

A Clear Road To Archangel, pp. 95-96

In such lyricism, Grigor somehow seems analogous to the cherry orchard in Chekhov’s play of that name; an almost bucolic symbol about to be chopped down as a more brutal era arrives.

Russia in Fiction does not know if Geoffrey Rose, actor before he was an author, was ever cast in The Cherry Orchard. But we like to think so.