In 1989, when Communist governments were thrown out of the power that they had usurped across Eastern Europe, the geo-political certainties of decades went with them. Almost overnight, multiple possible paths forward opened up; and fiction writers mapped them as much as did scholars, journalists and policy professionals.

John Hands’s Perestroika Christi was published in 1990. In that in-between bit during the collapse of Communism. Soviet control over the Central and East European satellite states had been lost, Germany was re-uniting —but what of the Soviet Union itself?

It is too easy, now we know, to see the collapse of the Soviet Union as inevitable by the dawn of the 1990s. It was not. Nor was it even the majority view of experts or governments that this was the way events would turn out.

Most analysis at the time considered what path the Soviet Union would choose to take. Would the end of the Cold War simply see cooperation between East and West, as the USSR focused on domestic reform? Would the loss of Eastern Europe bring back a hardening of the Soviet stance in relation to the West, with perhaps a more hardline leadership to replace Gorbachev?

May be reform and nationalist tension would lead to civil war in the Soviet Union? Or may be, more optimistically, the Soviet Union might join the European Union? Or even join NATO?

All of these options were on the table alongside, even before, that of the Soviet Union disappearing completely and irrevocably from the world stage.

As if these questions were not big enough, Hands’s Perestroika Christi went large, engaging with eternal questions, the two millennia old prophecies of the Book of Revelation, and the more recent prophecies of Our Lady of Fatima from 1917.

Perestroika Christi is a novel that particularly lends itself to the two questions that Russia in Fiction deploys in our reviews.

What is the book like? And what about its portrayal of Russia or the Soviet Union?

In short, John Hands’s first novel is a superior thriller; one of our favourites here at Russia in Fiction. (And that is from a very large selection).

Its take on the Soviet Union is pretty good for getting a sense of that uncertain in-between time of 1989-1990, but Perestroika Christi builds its prospective Soviet future on shaky factual foundations. And yes, we know it is fiction not political analysis, but even so the plot’s basis never looked that robust in terms of the details of its Ukrainian focus.

But hey, easy to be picky about details.

First of all, Perestroika Christi is a classic intelligent-yet-page-turning thriller.

Its hero is Catholic priest James Ryan. Clancy aficionados will have to do a double-take reading ‘Ryan did this, Ryan said that’ and so on. It’s a different Ryan, otherwise the Ryan-verse would spin into incomprehension. (Readers who have no idea what the Ryan-verse is will find it explained in our review of Tom Clancy’s The Cardinal of the Kremlin).

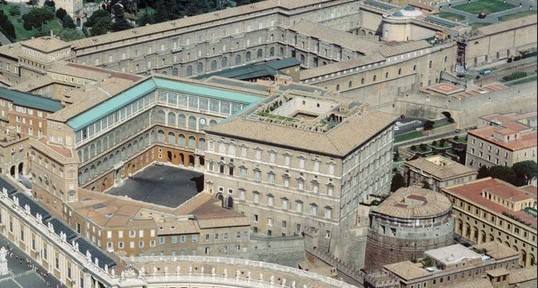

Father James Ryan is a young English priest catapulted into the role of the Pope’s Private Secretary, and into Vatican intrigue, particularly in relation to developments in the Communist world. The Pope, without being named, is very much a John Paul II figure, and one faction in the Vatican —the conservative one— is secretly backing Ukrainian nationalist separatist elements of the Catholic church in Ukraine.

There is also a traditional ‘who is the mole?’ plot element, with the presence of a KGB agent in the Vatican hierarchy being known to the reader, but their identity awaiting the big reveal at novel’s end. Oh, and a CIA agent is involved too, for a bit of balance.

As well as following Ryan in the Vatican City and on a well-drawn undercover trip to Ukraine, Perestroika Christi has an overlapping Moscow storyline to match. Deliberately to match. John Hands sets out similarities between Vatican and Kremlin in how his plot is set up, with the Moscow characters similarly split into reformist and conservative, realist and ideologically pure.

And just in case the reader doesn’t get it, early on chapter 7 begins:

Like the Vatican, the Kremlin is a walled citadel within a city, designed during the Renaissance by Italian architects.

Perestroika Christi, p. 60

And a couple of hundred pages or so later, a conversation between Ryan and a Communist-sympathising Italian journalist makes it plainer still.

‘One bureaucracy is the same as another?’

Bergantino snorted. ‘How long have you been in the Vatican?’

‘Six months.’

Bergantino waved a dismissive hand. ‘You know nothing, my young friend. Drink up.’

‘Then tell me what differences a Communist like you sees between the Vatican and the Kremlin,’ Ryan challenged.

Bergantino waved his forefinger at the priest. ‘There are two important differences, and you should never forget them if you wish to rise any higher up the tree. First, the Curia has a 330-year start on the Kremlin. Second, it is much more efficient. That’s why the Vatican is still going strong while the Communist bureaucracy has crumbled all over Europe’.

‘Doesn’t faith in God have something to do with the difference?’

‘Possibly. There are some members of the Politburo who still believe in Lenin’.

Perestroika Christi, pp. 328-329

Perestroika Christi has plenty of this sort of stuff, setting out big questions within the context of a thriller. More literary work might have done the same obliquely, within the sub-text of actions and outcomes. Here such questions are plain and centre.

Father Ryan is used by Vatican figures, to whom he has recklessly sworn obedience, to undertake a smuggling expedition, about which he has little knowledge and still less understanding, to Ukrainian Catholic nationalists. Talking with a Bishop of the underground church in Ukraine, Ryan asks

‘But surely, Bishop, one mark of the Catholic Church is that it is universal. It can’t be national at the same time.’

… ‘This is your Western thinking, Father. Christ tells us to love our neighbours as ourselves. When we love our neighbours, then we are good patriots, and also good Christians.’ …

‘I’ve been thinking about your nationalism, Bishop,’ Ryan said. ‘What I don’t understand is your attitude to the Russians […] You talk of loving your neighbour, but …’ He let the words hang in the air.

Perestroika Christi, pp. 170-172

In terms of its representation of the Soviet Union in 1990, geo-politically Perestroika Christi enters the widening field of options, particularly in its representation of a Soviet president intent on closer relations with the West, perhaps even eventual membership of the European Union.

At this time, in the real world, Mikhail Gorbachev was talking eloquently if vaguely about ‘our common European home’.

As set out in his book, Perestroika and New Thinking for Our Country and the Whole World, which Russia in Fiction purchased in the Soviet Union in 1988.

But the possibility of Soviet collapse, although only a year away from actually happening, is largely absent from Perestroika Christi. Hands has the Ukrainian nationalist movement negotiate with the Kremlin on the basis of 12 demands; not one of which is straightforward Ukrainian independence.

In August 1991, the parliament of Ukraine declared independence from the Soviet Union; a declaration confirmed by 92% of the population in a republic-wide referendum on 1st December.

And the central premise of the plot of Perestroika Christi seems too remote from real world possibilities for Russia in Fiction’s preferences. The idea of a Catholic-led independence movement reads as a transfer of real-world events in Poland during the 1970s and 1980s, into the markedly different religious, ethnic, and political setting of Ukraine, where the church had been repressed for decades, and even the practising Christians in the population were to be found in several denominations, notably including Orthodoxy.

Hands’s descriptions of Soviet life and politics in 1990 are more convincing. His description of the speeches at the Congress of People’s Deputies —the new version of the Soviet parliament, instigated by Gorbachev in 1988 as a major step towards democratising the USSR— could have been taken from a transcript of the real thing. The arguments of reformers, conservatives, and those in between are set out; and the fictional names can be substituted with real ones in the minds of readers with sufficient knowledge of those times.

There is Filipchenko (or is it Yeltsin?) demanding an end to the privileges enjoyed by Party functionaries, and provocatively asking the Soviet President

‘If the changes in eastern Europe were inspired by the Soviet Union’s policy of perestroika, have you thought about applying the policy of perestroika to the Soviet Union?’

Perestroika Christi, p. 62

There is ‘the President’ whose behaviour in the chair of the parliament is archetypically Gorbachevian, as he.

sat there, occasionally interjecting to correct a matter of fact, like a benevolent headmaster with a gifted but erratic pupil

Perestroika Christi, p. 62

And there is Leonid Dobrik (or is it Yegor Ligachev?) declaring that it was

‘Filipchenko’s version of perestroika that was bringing the country to economic crisis and political chaos’.

Perestroika Christi, p. 63

Perhaps inspired by its subject matter, reviews of Perestroika Christi by some very knowledgeable people called it ‘prophetic’ (Sir Rodric Braithwaite, British Ambassador to the Soviet Union and then Russia, 1988-1992), ‘unerringly perceptive’ (the late Professor Peter Frank, British academic and Channel 4 Russia-expert), and ‘extraordinarily prescient’ (the late Professor Norman Stone, in nominating Perestroika Christi as his Book of the Year in The Guardian).

If you want more such positive snippets from reviews, helpfully the author’s own website supplies them.

Russia in Fiction prefers to major on what a cracking and well-crafted thriller Perestroika Christi is; as indeed is Hands’s second book, another Ukraine-centric novel, Darkness at Dawn.